Our cookies

We use essential cookies to make our website work smoothly for you. To make sure we're always improving, we'd like to use analytics to track how people use the site. We won't set non-essential cookies unless you give us permission. You can find more information about all the cookies we use in our Privacy and Cookie Policy.

Some cookies are a must for our website to function properly. If you turn off essential cookies, it may affect how you experience our site.

The non-essential cookies we use help us understand how you use our website and make improvements to enhance your experience.

Happy Place: How to Create a Positive Parent Culture

Parents are the biggest influence on their child so it is vital to have them on side and supporting coaches. Three experts from the sports sector give us their advice on how to create a positive culture.

by Mike Dale

Grassroots sport could not exist without parents. They are the taxi drivers, payers of subs, purchasers of equipment, sources of inspiration and support, rattlers of fundraising tins and often the reason why a child was motivated to pick up a racket/kick a ball/swim fast/ride a horse in the first place.

They are, of course, the biggest influence on the child being coached and their presence within the coaching environment is considerable. That influence is usually beneficial to the child’s sporting development and wellbeing, but occasionally they can act in a way that’s detrimental not only to their own child, but to the enjoyment of team-mates and opponents.

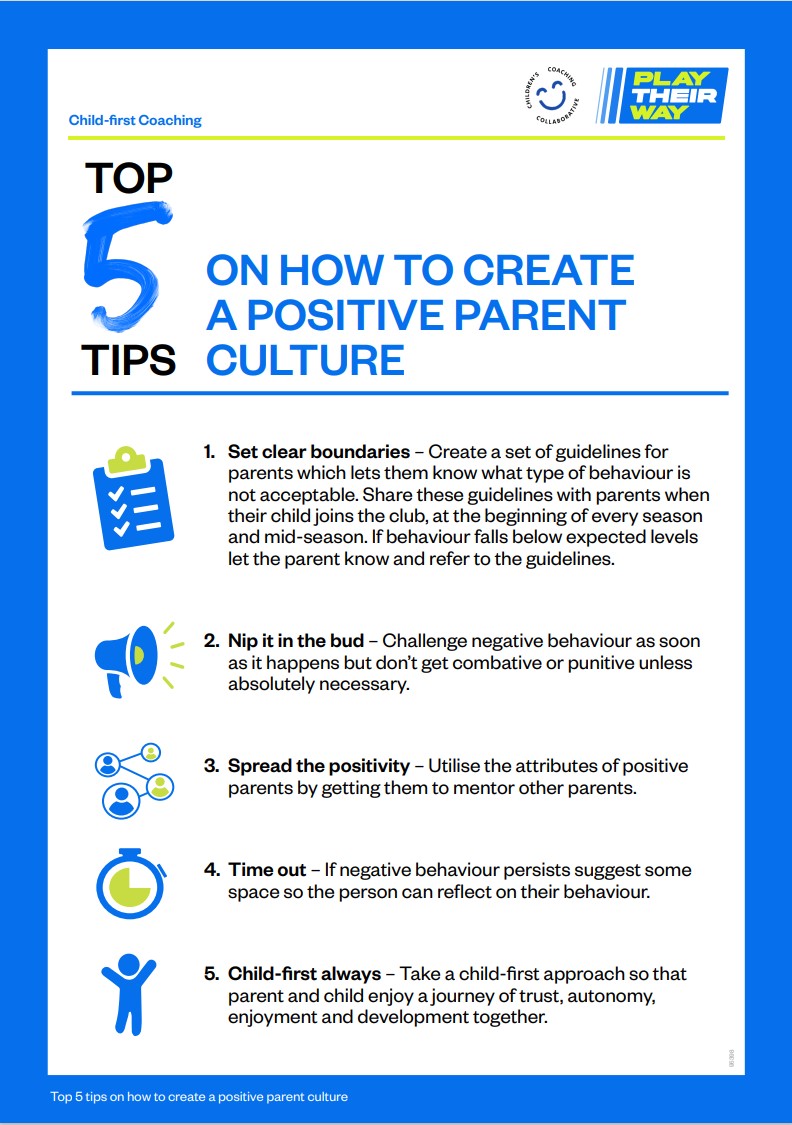

Many potential issues can be mitigated by taking a preventative approach; establishing a positive culture and setting a benchmark that a coach can later refer back to if behaviour falls below expected standards.

An ideal basis for those benchmarks is the principles of the Children’s Coaching Collaborative: that every child has the right to play, to develop and to be heard, regardless of their age, gender, background or ability. The three key ingredients of this approach are:

Voice

Children and young people have the right to express their views which are acted on together in a meaningful way.

Choice

Children and young people have the right to play and shape what play looks like.

Journey

Children and young people have the right to develop holistically, in their own way.

Although child-first coaching will look different for every child, the focus on voice, choice and journey should be consistent. Cultivating a positive parent culture is a key part of working successfully within this child-first framework.

The NSPCC’s Child Protection in Sport Unit (CPSU) supports national and local sports organisations with safeguarding, capacity building, good practice and achieving the best possible outcomes for children and young people. Setting expectations of parents is a key factor in achieving this aim.

“Sometimes the role of parents, grandparents, carers or key adults in a child’s life doesn’t get celebrated as much as it should,” says Michelle North, Associate Head of the CPSU. “But when parents’ enthusiasm gets the better of them, it can have a terrible impact on children and young people.

“Thankfully, they are in the minority, but what I’ve noticed within my practice is we’re not very good at telling them the behaviours we want to see. Often, they don’t understand the impact they’re having and will misperceive their behaviour as encouragement. Holding up a mirror to that is sometimes quite difficult.”

Voice and Choice

Giving children ‘a voice’ (opportunities to share their views) and ‘choice’ (allowing them to shape how they play and participate) offers coaches a great way to ‘hold up a mirror’ to parents and expose them to the impact of their behaviour. Hearing directly from their own children’s mouths about what they do – and don’t – want from those on the touchline can be quite eye-opening.

This is an element that often gets missed – talking to children and young people to ask what their feelings are,”

Michelle North, Associate Head of the NSPCC's Child Protection in Sport Unit

says Michelle. “The power of reflecting that back to parents can often make them sit back and say, ‘I had no idea!’ If their young people say something makes them feel really uncomfortable, that has the real power to effect change.”

The NSPCC’s CPSU runs workshops for clubs which gives coaches, parents and young people space to air their views.

There is a well-known expression which will ring true for all parents: you’re only ever as happy as your unhappiest child. Thus, if the coach keeps the children happy, the parents will be happy, thus they’ll support what you’re doing, creating a positive environment.

Keeping the children happy comes back to the child-first coaching principles of giving them a voice and choice.

As Michelle explains: “There’s been much research in sport, and other sectors, that shows we don’t talk to children and young people about their experiences very well. We do it tokenistically, or when we do speak to them, we don’t respond to what they’re telling us.

“If we’re able to talk about their experience of a session or a match – what they liked or didn’t like about it, what they’d like to do differently next time etc – they will feel they’re genuinely being listened to and that the coach is helping to build a pathway to where they want to be. It builds an awful lot of trust. There’s an incredible power in that.

“Ultimately, we want to generate a lifetime love of sport and physical activity – and children will only keep coming back if they enjoy it. If coaches have that open interaction with the children and make changes based on what they want, they’ll feel valued. Their parents or carers will see that, and it will then be pretty hard for them to argue that that isn’t great for their young person.”

Flyerz Show the Way

Hockey coach Lizzie Edgecombe takes things one step further with her fortnightly Bristol Flyerz inclusive, pan-disability sessions for participants who range in age from 5 to 27.

Lizzie encourages parents to put bibs on and cross the white line. They are fully, physically involved with the activities. She says: “Some parents play every week and support other children as well as their own, others have children who are bit more independent, so they do their weekly shop over the road instead – either way is absolutely fine. It’s just a chilled out atmosphere. We have so much fun.”

Joanna Herbelot, mother of 12-year-old Anaïs who has additional needs, says the Flyerz sessions are a “wonderful free-for-all.” She adds:

The inclusivity is amazing. It is so welcoming and friendly. Anaïs’s grandma even joined in last week. Including the parents like that makes the children feel safe and secure."

Joanna Herbelot, Parent of Bristol Flyerz participant

“I use it as part of my weekly fitness. We start with a warm-up, then play loosely hockey-based games like ‘Stay in the D’, hop on the spot or tag. It encourages children with additional needs to keep going and build resilience. My kids love it when I join in. It sounds like it shouldn’t work, but it does!”

Lizzie says this sort of positive parent culture wasn’t meticulously crafted, but more “instinctive” on her part. For other coaches, it has to be worked at.

Setting Expectations

The start of a season, or when a new child joins, can be key moments in developing a positive parent culture. If a coach has set out some guidelines, it allows him or her to refer back to them if behaviour falls below expected levels. This can extend to written codes of conduct if necessary; whatever the coach feels is necessary to lay down ground rules. These can be adapted and reminders issued mid-season if necessary.

The first few sessions or matches are key to setting standards. “Early danger signs can be really small,” explains Michelle. “It can sound a bit petty, but you might say, ‘We don’t want people shouting at the coach or referee.’ If it isn’t challenged early on, these behaviours can become normalised. It then doesn’t take much for an offhand comment to escalate to shouting, swearing and even getting physical.

“The key is being really clear about what you want to see and as soon as there’s behaviour you don’t, reminding parents about the code of conduct you sent or agreements you made about expectations. Often, people will say, ‘Sorry, I got carried away.’ Start as soon as you see or hear something that worries you. It sets the tone.

“The more you talk about it, the more power it has. At some point the penny will drop, but it might take a little while.”

Every coach will recognise stories of ‘the bad egg’ whose negative behaviour is embedded within their personality, refuses to change and can have a toxic effect on those around him (or her). It’s important not to take a combative or punitive approach to this until absolutely necessary. Can you channel their passion? Could they help out? Could other, more positive parents befriend or mentor them? Could they be given space to reflect on their behaviour?

Sometimes, though, someone’s influence is so persistently negative that the best thing for the children is to remove them. “We hear lots of stories, but these kinds of behaviours occur in sports you would never imagine – it's across the whole spectrum,” reveals Michelle.

Whilst there may no escaping the occasional ‘bad apple’, coaches can mitigate against this and establish a positive culture with their parents by setting clear boundaries, utilising the attributes within the group behind the touchline and, most importantly, taking a child-first approach so that parent and child enjoy a journey of trust, autonomy, enjoyment and development together.

For more resources on involving parents, carers and legal guardians in sport check out the CPSU website.

Other resources you may like...

About the contributors

Lizzie Edgecombe is Development Manager for Access Sport’s Changing Places work focusing on Bristol and specialising in disability inclusion. She is also a volunteer coach, leading Bristol Flyerz hockey sessions for children with special needs and disabilities.

Michelle North is Associate Head of the NSPCC’s Child Protection in Sport Unit. As well as responsibility for the organisation’s CPSU staff across England, Wales and Northern Ireland, she manages relationships with sports councils and key partners and drives strategy. She previously worked in the NSPCC’s Safeguarding in Education Service and before that was an Education Welfare Officer and a senior manager with responsibility for prosecutions and case management for a local authority.

Joanna Herbelot is the mother of 12-yar-old Anaïs, who attends Bristol Flyerz sessions led by Lizzie.

SHARE THE MOVEMENT

Help spread the word by sharing this website with fellow coaches!